Recently – and this will come as a shock to those of you who know me well – I have been reading a book. It’s not something I make a habit of. In fact I can’t off-hand remember the last one I saw through to the end. But you know self improvement is all the rage these days and I thought it was worth a crack.

The book in question is one I should have read long ago…a quintessential story for North American birders. I’m actually not sure how I avoided it for so long. Probably by avoiding books in general, but that’s beside the point. The book I’m reading is Kingbird Highway by Kenn Kaufman.

Kingbird Highway is an autobiographical adventure tale about a bird-obsesssed midwestern teen who drops out of highschool and embarks on a cross-country birding epic. Kaufman’s story features sketchy hitchhiking, questionable company, and subsistance on coffee and catfood. It is such a fixture of birding lore that I knew most of the details long before I cracked the cover.

Kaufman’s travels evolve into an attempt to break the big year record for North America, seeing more bird species in a calendar year on the continent than anyone before. In doing this he cemented himself as one of the best known figures in this niche subgenre of birding. Actually in birdwatching as a whole.

What resonated with me about Kaufman is that although he is known for his competitive birding feat, his introduction to the hobby was exactly the same as mine. It was probably the same as that of most birders in my generation, and in his, and in the ones between and before. He was simply a curious kid with encouraging parents and access to an old bird book. He spent time in his backyard getting to know the birds that lived there, then gradually went further afield in his neighbourhood, then beyond.

This may seem like the most logical way to get into birdwatching, but the current landscape is very different. Today many new birdwatchers enter the hobby by joining Facebook and WhatsApp groups, signing up for Discord servers, and downloading a bevy of apps. These days you can take your first foray into birding without leaving the couch or, in fact, seeing a bird.

I am aware that I’m perilously close to uttering the phrase “back in my day”, so I’d like to be clear that I’m not in the habit of railing against new technology. Technology has always played a role in the hobby, and it has always evolved. I’m sure there was outcry when birders moved from rifles to binoculars, and objections to phone chains, email listserves, and Yahoo! groups (remember those?). Modern birding technology is awesome, and I’m sure most new birders do, in fact, see birds at the outset.

My beef (you had to expect I had one) is not with the technology, but with the effect this new environment may or may not be having on birdwatchers and the broader birding community. It’s something I’ve been thinking about for a long time but found very difficult to articulate. I thought maybe it was all in my head, but recent conversations with unsuspecting victims (I mean like-minded individuals) have convinced me that there may be something to it.

In an attempt to put my finger on that thing I can’t quite put my finger on, I think I’ve narrowed my (very nebulous) theory down to three key points: expertise, ego, and emphasis. God I love it when alliteration sneaks up on you. I’ll try to explain what I’m on about, and then I’ll desperately try to make a point. Here goes.

Firstly I think the way we are introduced to birding today has affected the way we accumulate knowledge (or expertise…I did have to massage this one a little). It pains me slightly to admit that I learned to bird long before the internet was a household convenience, so my method of learning, like Kaufman’s, was primarily observing birds in the field and then leafing frantically through a beat-up field guide or seeking input from a more experienced birdwatcher (in my case, my father).

Today new birders are instantly bombarded with more information than I could ever have imagined. The smartphone in your hand puts my ancient field guide (and, if we’re honest, my father) to shame (sorry Dad). It may seem a great advantage to have this sort of resource at your fingertips, but I’m not entirely convinced.

I think that this shift in the way we access information has also shifted the bulk of our bird learning from practical (in the field) to theoretical (behind a screen). In an age where we are accustomed to getting our information from our phones and computers, we’re just far more likely to turn immediately to our devices than to actually study the animals in nature. There’s another problem too.

Not only is the information you access online variably reliable, but the sheer volume means that new birdwatchers are thrown directly into the deep end at first glance. Gone is the natural progression of learning birds as you observe them in your yard or neighbourhood, replaced by a barrage of bird information with little sense of commonality or context. It’s simply too much of a good thing.

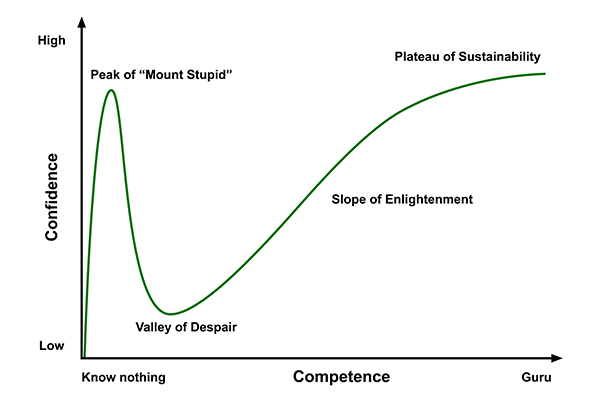

You’d think that any new birder confronted with this absolute glut of information would feel that they could never aquire enough of it but I think, for many, the opposite is true. I think that easy access to all this knowledge makes us feel pretty darn clever, and exacerbates something called the Dunning-Kruger Effect (thanks BH).

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is the thing that makes you think you’re an absolute pro after only a short period of learning something new. Once you acquire some knowledge about the subject it feels like you’ve become an expert, even though you still have volumes more to learn. You can think of it as not knowing how much you don’t know.

This effect has always existed in birding, but it seems to me that if you’re a bit of a hot-thumb on the apps and you’re six months further along in your learning than the next person in your regional Facebook group, it’s even easier to feel like an expert than it used to be. Which brings me to my next point: ego.

We all have one. I won’t sit here with a straight face and tell you I’m immune. We all have an ego, we all enjoy when it gets stroked or inflated, and we all know that one of the best tools for doing that is social media.

Birding Facebook groups (and other online communities) are a spectacular example of this. Like all social media they allow you to assert yourself with great confidence (and frequently, it seems, rudeness) and never deal with the fact that you may be wrong. Being first and looking smart takes priority over being right or accurate, and all of those often seem more important than being helpful or polite.

On the flipside, when you learn by connecting with other birdwatchers in person, you need a somewhat more humble approach. If you’re rude to a new birder, you’ll see the effect of that rudeness on their face. If you confidently state things that are untrue, somebody more experienced than you will take you to task. If you go with others to new places, you are reminded of how much you don’t know. Face-to-face interaction with other birders in the field is an ego-deterrent.

Social media affects our priorities in other ways too, and this brings me tidily to emphasis. The thing about going out into your backyard and appreciating a robin is that it doesn’t score you a lot of likes on Facebook, or allow you to make an exciting rare bird post on Discord. For that kind of validation, you need two things.

First, you’re absolutely going to need a photo. I won’t take the deep dive into the bird vs. photographer debate here (as a birder and photographer myself), but suffice it to say that the rapid rise in the number of fanatical bird photographers who place little emphasis on the birds themselves has caused some tension in recent years.

Second, you need to see something rare. Perhaps the thing that has most struck me lately is that the emphasis on seeing rare birds seems to enter a person’s birding journey at a far earlier stage than it once did. Maybe it’s the Pokemon GO era, or maybe we’re just all seeking a little extra validation as the world crumbles, but it feels to me like there’s a whole generation of birders that are chasing mega rarities before they can identify the ten birds in their local park.

This is where I’m going to try to make a point, so bear with me. I am fully aware that the logical response to all of this is “who cares?”. People should be free to bird how they want, and there’s no reason it should make any difference to me. A big part of me agrees with that. But there’s this nagging, niggling voice that tells me that all of these changes are causing people to miss something, and that something may just be the best part of birdwatching.

When seeing rare birds and chasing online validation become the main objectives of birding early on, people seem to skip over the part of birdwatching where they actually watch – and subsequently become familiar with – the birds that are common and close to home. Instead of an act of connecting, birding becomes an act of collecting, or competing.

If you ask me, that connection with birds is truly the best part of the hobby. I’ve been fortunate enough to see a few rare birds, but my favourites will always be the ones I grew up watching in my backyard. I never tire of taking a few moments to check in with the chickadees, and it never fails to make me smile. Most days I’d far rather do that than chase some lost European songbird across the province.

Not only is this type of familiar birdwatching excellent for your mental health (yes, there are studies), but it will make you a better birder, too. Studying common birds helps you practice field identification, develop a feel for shape and impression, and learn where those birds fit in their natural context. You develop a repertoire of birds that you know well, and it becomes easier to assimilate new birds into that bank. You learn how to learn birds, and it is an enjoyable and rewarding process.

This slow birding even makes you a better rarity chaser, if you decide to go that route. Knowing your common birds allows you to place those rare ones in context. It helps you understand why they’re here and why they’re special, rather than just assuming they’re good because other people are excited. It lets you really see and appreciate those birds, rather than just ticking them on a list. It can even help you find a rare bird of your own.

It’s clear that our technological birding landscape is not going away. Nor should it. But I think it’s worthwhile to consider how we interact with these novel tools, and how they affect our interactions with each other and with the birds themselves. In many ways it’s a better time than ever to be a birdwatcher, but it may be the most challenging time, too.

What I’m trying to say is that I hope, if you’re a new birder, you’ll take time to build connections with the birds that are closest to you and not worry so much about chasing every rarity, collecting online accolades, or becoming an expert overnight. In fact, I wish birders of all skill levels would do the same. And if you’re an experienced birder, remember that you were once a new birder who would have appreciated a supportive, helpful, and welcoming community far more than just a handful of answers.

I love knowing that Kaufman, an absolute all-star of the competitive birding scene, didn’t start birdwatching by chasing rare birds. He started with a genuine interest in the birds outside his window, and he writes as passionately about the kingbird in his backyard as every bird he saw on his record-setting big year. His target may have been a number, but his emphasis was always on the birds.

At the end of the day, I have no business telling anyone what they should or should not do. I’m just another weirdo who does birding, and you should probably just dismiss this as sentimental (and biased) rambling. I suppose it’s just my way of expressing my selfish desire that birdwatching is for others what it has always been for me. This is what I get for reading a book.

One reply on “The State of Birding, and the Weirdos Who Do It”

[…] very long time ago – like nine months – I made some opinions about The State of Birding and the Weirdos Who Do It. Those opinions included a few brief thoughts on birding apps, and at the time I thought I would […]